Disney: From Offensive to Progressive?

If you’re a human who’s been living in the 21st century and not hiding out under a rock, you’re probably familiar with at least some of the recent Disney movies. There’s the new Beauty and the Beast remake, which, while leaving all the problematic holding-Belle-hostage-till-she-falls-in-love shit, also features the first genuine gay character in one of the studio’s films (however subtly), so #progress; Moana, which revolves around Pacific-Islander characters; Zootopia, a social commentary that’s kind-of-sort-of about bigotry and racism and police prejudice; Big Hero 6, which takes place in “San Fransokyo” with a diverse cast of characters; and Frozen, which has all-white characters to keep the white people from rioting (but hey, at least the princesses are badass and don’t get rescued by men!). On the TV side of Disney’s maniacal magical empire, there’s the first Latina princess via the eponymous Elena of Avalor (although the fact that they broke tradition and stuck their first Latina princess on TV rather than giving her a proper in-theater debut is a little side-eye-inducing); Doc McStuffins follows the misadventures of a young black girl, who is following in her doctor mother’s footsteps; Good Luck Charlie featured the channel’s first openly gay couple in an episode a few years ago; and the channel just announced the reboot of the much-beloved That’s So Raven, this time featuring Raven as an all-grown-up divorced single mom. So what does all of this mean? Disney really wants you to know how #progressive they are. And, okay, maybe they’re also making this push for representation because it’s the right thing to do and they’ve finally realized that—but c’mon. Disney, despite its pixie-dust, is still a corporation. While I’d love to believe Disney’s brand of diversity is all in the name of positive representation and rainbows and smiles, it’s more likely that they’re motivated by simple greed and good PR. And, hey, that’s fine. Representation’s representation. I’ll take what I can get, even if the progress does have a hashtag in front of it.

Anyway, as a certified Disney Dork (what? did my anti-Disney cynicism confuse you?), I’m happy to see the continued evolution of their characters and storylines. In fairness, Disney’s actually been working on better representation and diversity in their films/shows since before many Twitter #progressive activists were born. The 90s saw Aladdin, the birth of the headstrong, feminist princess via Belle, Halloweentown (hey, showing witchcraft in a positive light is pretty damn progressive!), and Mulan, not to mention ballsy choices like including the whole religious-hypocrisy thing in Hunchback of Notre Dame—and, speaking of, how badass was Esmeralda?! While those films may not have been flawlessly progressive (e.g., the whole Stockholm vibes of Beauty and the Beast; the bizarre and offensive lyrics to that one Aladdin song) and there were well-intentioned but ultimately tone-deaf stumbles (like with the stereotypical, historically inaccurate Pocahontas), the 90s were, overall, a helluvah step in the right direction—and that direction carried on into the early ‘00s, with films like Brother Bear, The Emperor’s New Groove, Lilo & Stitch, and The Princess and the Frog, as well as Disney Channel’s Kim Possible, The Proud Family, American Dragon: Jake Long, The Suite Life of Zack and Cody (whose single-mom-led family dynamics were one of few on TV that I could relate to), and yes, That’s So Raven (not to mention films like Twitches and The Cheetah Girls). In fact, Disney has been putting to shame many other studios and networks, whose own representation has been a slow, teeth-pulling process—despite ample evidence that audiences won’t be scared off by movies led by actors of color, women who don’t weigh 110 pounds, or LGBTQ characters. In that regard, Disney could be a rare, shining example of progress and diversity.

And that’s crazy—because Disney used to be the exact opposite.

Before the early 00s, before the 90s, back into the shoulder-padded trenches of the 80s and, before it, 70s, 60s, 50s and so forth, Disney was kind of like that racist, sexist, homophobic uncle you don’t speak to anymore.

That’s right, kiddos: Disney used to be hella ignorant!

But I don’t need to patronize. There’s a good chance you already know about Disney’s history—or at least some of it. For instance, I’m going to bet you’ve seen The Little Mermaid somewhere between one time and two dozen, and so you may realize—looking back on it with clear adult eyes—the terribleness of Ariel. I mean, for fuck’s sake, she literally gives up her voice for a man. And it’s framed as a bona fide romance! Throughout much of the movie, she acts like a ditzy, clueless, lovesick puppy at best and annoying idiot at worst, all in the name of a guy she doesn’t know and who doesn’t know her (though Prince Eric, in fairness, is pretty fucking glorious).

And let’s not overlook the queer-coding of drag-queen-from-under-the-sea, Ursula. Sadly, The Little Mermaid isn’t the first or only instance of a queer-coded villain popping up in a Disney movie, and it was a trend that continued into their 90s Renaissance with characters like Pocahontas’s Governor Ratcliffe, Hercules’s Hades, and Aladdin’s Jafar. And, of course, The Little Mermaid is not the only—nor the most egregious—example of a problematic Disney princess.

You’ve probably seen classics like Cinderella and Snow White, which involve passive princesses and—in Snow White’s case—some disturbing implications (I mean, kissing an unconscious, kinda-dead princess is nonconsensual and necrophilia-ish, so . . . there’s that). You also should be familiar with Peter Pan, which, like Cinderella and Snow White, is regarded as a classic and still shown to children—despite all of its overt racism. If you don’t know what I’m referring to, let me put it simply: The portrayal of Native-Americans in Peter Pan is forty different flavors of fucked up. Just look at how they’re drawn!

And with musical numbers like “What Makes the Red Man Red?”, it seems the film took tremendous joy in its appalling racial humor and stereotypes. SMDH.

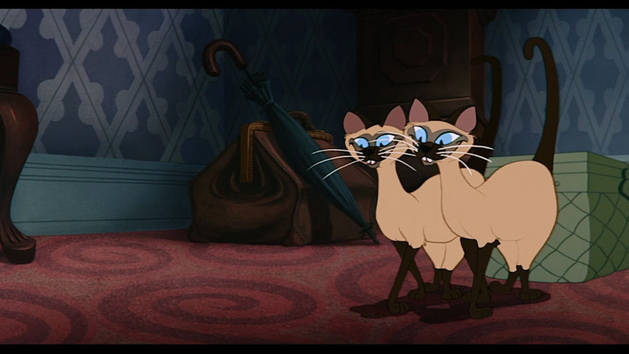

The thing is, racism (and sexism) in Disney movies was once a time-honored tradition, as much a mainstay as magic and cute animals—like in Lady and the Tramp, with its Siamese cats playing into Asian stereotypes that rival even I.Y. Yunioshi in Breakfast at Tiffany’s. (Not-so-fun fact: The Aristocats also has a feline Asian stereotype. What’s the deal, Disney?)

The crows in Dumbo are also considered to be black stereotypes (with the lead crow—and the only one that was voiced by a white actor—originally having been named “Jim Crow”), though some point to their intelligence, wit, and sympathy for Dumbo as virtues that somewhat lessen the racism—or, at least, make it easier to swallow. In Fantasia, there are two black female centaurs—Sunflower and Otika—who are subservient to their white centaur counterparts, cleaning and caring for them. In fact, the depiction of these two is so fucked up that Disney ended up removing them from the film altogether to avoid controversy.

Plus there’s several cartoon shorts featuring such grotesqueries as Mickey donning blackface and stereotyping ad nauseum.

And don’t even get me started on Disney’s long and storied history of fatphobia (which often intersects with their homophobic queer-coding, as with Ursula and Governor Ratcliffe)—from the impossible thinness of their female heroines to mocking/shaming/stereotyping the few rare larger characters that have been included in their movies and shows (as with Disney-Pixar’s Wall-E), it’s enough to help kids (particularly young girls) develop some pretty shitty feelings about their bodies and beauty in general. And, sadly, despite the recent strides Disney has made, their impossibly-thin heroines and casual fat-shaming are still prevalent (and likely aren’t going away any time soon).

Then there’s Song of the South.

You may be familiar with this 1940s film because of its infamous racism, but, assuming you aren’t, let me sum it up: Set in Reconstruction-Era Georgia, Song of the South is a simplistic and idyllic take on race relations in the South during the 1870s, wherein black people are seemingly subservient to white people because they want to be—a film that, according to the NAACP’s Norma Jensen, who saw it at a press screening in 1946, “contains all the clichés in the book.” The movie is so racist that Disney has actually never even released the whole thing on home video in the US—which is saying something because, as you can see by how perfectly fine they are to circulate their other racist old films, that’s not something they do often or carelessly. (They have, though, released it on home video in parts of Asia and Europe, which is pretty disappointing.)

On the bright side, Song of the South nabbed the first Oscar ever awarded to a black male actor—although it was an honorary one. James Baskett, who played Uncle Remus in addition to providing voice work for the film’s animated sequences (this being back when Disney was hopelessly in love with combining animation with live-action films), received the award—something Walt Disney campaigned for, calling him “the best actor [. . .] to be discovered in years.” So, that’s pretty cool.

Less cool? The fact that James Baskett couldn’t attend the premiere, because—since the premiere was held in Atlanta, which was then a segregated city—he wouldn’t have been able to take part in the festivities.

Seriously, fuck that.

What’s amazing about all of this is that Disney hasn’t completely distanced itself from its past. You would expect them to sever ties with any of their old films that perpetuate stereotypes now that they’ve decided to be #progressive, but, for the most part, they totally haven’t. Merchandise for pretty much all of these films (excepting Song of the South) is readily available at their stores; many of these films have attractions based on them at the Disney theme parks; Disney still sells them on home video, and allows them to be rented and streamed; and many of the songs from these films are included on their compilation CDs—in fact, “The Siamese Cat Song,” the infamous tune sung by the Asian caricatures in Lady and the Tramp, was included on two of the Disneymania albums from the early ‘00s, with one version being sung by the Duff sisters (does it make it more or less racist to have two white girls sing it? You decide). “When I See an Elephant Fly,” the problematic song sung by the crows in Dumbo, was also covered by white people on one of the Disneymania albums.

Even Song of the South continues to be spotlighted—like with the Disney parks attraction Splash Mountain, based off the film, or the song “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah,” which continues to be shoved at us despite being from a racist film and being arguably as inane as the much-reviled “It’s a Small World After All.” (Yes, if you were wondering: “Zip-a-Dee-Doo-Dah” was indeed covered on a Disneymania album. Three times. And one version was sung by Miley Cyrus!)

I’m sure you can figure out the reason why Disney hasn’t quite managed to shut the door on that lil chapter of its backstory, but I’ll spell it out for you all the same: money. Yes, Disney could pretend like all of its problematic history never happened—but that would mean forgoing any future opportunity to make a buck off these same problematic properties, and why the fuck would they do that? Instead, they’ll just keep Song of the South in a hidden little closet—leaving the door ajar just in case. But the other films won’t even be in a hidden little closet: they more or less get to mingle with all the current, respected, progressive Disney films, and continue to be revered as part of Disney’s Teflon legacy. Which is . . . batshit, pretty much. (And no, occasionally putting these films in the “Disney Vault”—where Peter Pan is currently located, along with Lady and the Tramp—is not the same as doing away with them or sticking them in the less-cushy Disney closet with Song of the South. I mean, for fuck’s sake, movies go in and out of that damned vault faster than Disney produces sequels. And also, the vault’s purpose is far from an anti-racism stance.)

Look, I’m not saying I’m in favor of doing away with all of Disney’s old, problematic films. They’re classics; their existence cleared the way for modern Disney’s existence; their animation is spectacular, and they do have their share of good—or even great—parts. At the same time, viewing them should come with an asterisk, and I’m not certain whether or not some of them should even be viewed by kids of the twenty-first century—at least not without a long conversation before or after. Because kids do view the world and the people within it through the lens of what they’re taught and shown, exposing kids to, say, the passivity and stereotypical femininity of old Disney princesses could lead them to have a specific view of women that’s harmful and inaccurate—and the same is true for Peter Pan’s racism. But that’s a debate for another time. For now, let’s focus on Disney.

To recap, Disney is desperate to prove their #progressive cred (with frequently mixed results), but also continues to hawk their anti-progressive old movies—after all, even the ones that should be banned (and practically are, at least in the US) still have theme park rides. And while I understand not wanting to do away with classic films like Peter Pan, I also think they could, at the very least, do something to lessen the hypocrisy and fakeness of being progressive only to an extent.

Some obvious solutions include re-theming Splash Mountain: leaving the ride intact but switching out the Song of the South touches for a more modern, relevant, and—you know—not super offensive movie. Hell, they could re-theme it to Moana. How cool would that be? And it’s not like re-theming is something they don’t do: it happens literally all the time—in fact, it’s happening right now in Disneyland, as the Tower of Terror goes under the knife for a Guardians of the Galaxy re-theme, and it happened just last year with Epcot’s Maelstrom ride being transformed into a Frozen-themed spectacle. (And yes, the fact that they re-themed those two innocuous rides before Splash Mountain does indeed infuriate me.)

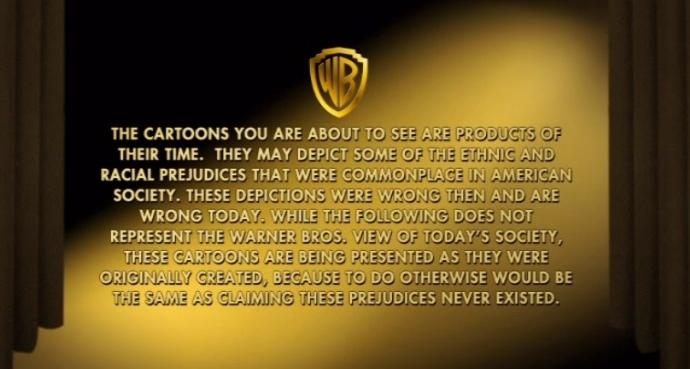

If they’re going to continue to air their offensive films or allow them to be streamed/purchased on home video, some form of onscreen discretion warning would also be nice—which is exactly what Warner Brothers chose to do with their bigoted cartoons.

Disney could also move away from the shameless promotion of their old, problematic films by having less merchandise themed to those movies, and including them less often in their various firework shows/parades/assorted montages/compilation albums. They don’t have to do away with them completely, just move the focus off the problematic and onto the progressive. And, if they want to keep the nostalgia of their old films, all they have to do is switch out those films for some other oldies that aren’t offensive—like Alice in Wonderland or One Hundred and One Dalmatians.

Finally, if they’re going to do a live-action remake of some of the problematic oldies (and they really shouldn’t, but you just know they will), they should use the opportunity to make the films more modern and, yes, progressive. They had that chance with the new Cinderella, but while they made some positive changes, they pretty much squandered it. Nouvel Beauty and the Beast was also something of a missed opportunity—the gay character received a mixed reaction, and while they did add plenty to the story (including, inexplicably, teleportation), and gave new layers to both Belle and the Beast, they did little to change the whole imprisonment/Stockholm thing. I can only hope that when the live-action Little Mermaid comes around (oh yeah, bitches: that’s happening), they decide to update Ariel and make her into a feisty feminist warrior princess more on par with their newfound values.

I would love nothing more than to get onboard with Liberal Disney, because I do appreciate their strides in diversity—especially since they’ve stood by those choices in the face of typical pearl-clutching-conservative backlash—but in order for them to be truly progressive, they have to do more than make a villain’s sidekick queer. And if that means severing ties with Song of the South once and for all, shelving much of their problematic backlog, diversifying their Disney princesses (in terms of not only race but sexual orientations and body types), and using their cash-grab live-action remakes as a chance to right some wrongs and maybe make some statements, then I say, bring it on.